Cop 21: last call for the Earth

Energy 7 December 2015Despite the Paris terrorist attacks that killed 130 people, French President Francois Hollande had no doubt on confirming the United Nations Climate Change Conference opened last Monday 30 November 2015. Heads of State summoned expecting to sketch compromise: US President Barack Obama, Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi are all together among the leaders set to address the conference on its opening day. Indeed, the grand goal of this 21st Conference of Parties (COP21) on climate change is to negotiate a global climate treaty to enter into force in 2020. In the desired worldwide treaty, all countries are expected to commit themselves to curbing greenhouse gas emissions and to limiting global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) by the end of the century (compared to pre-industrial levels).

The UN Conference has therefore great expectations, because so far no conference has led to a worldwide accepted treaty on environmental standards. While it is too early to sum up its outcomes, yet it is the moment to set the status quo and infer on its conclusions.

As far as the two goals are concerned, the 2-degree-target was proposed by the international community at the Climate Change Conference in Cancun, Mexico, in 2010. Scientists agree that if global warming were limited to less than 2 degrees Celsius, its effects could be kept manageable. Regarding the other target, the growth of global carbon emissions virtually stalled last year after a decade of rising rapidly, likely resulting from the economic slowdown in developed countries.

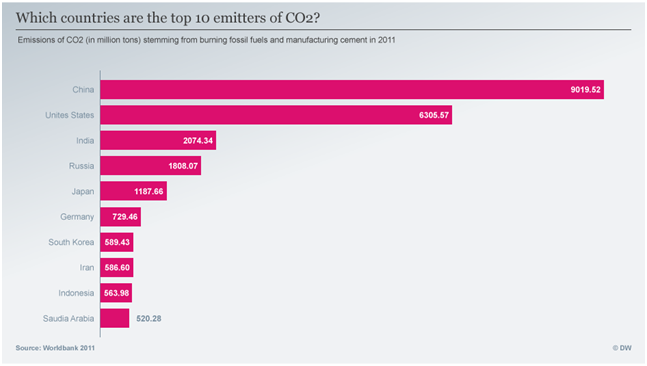

According to the Netherlands environment agency the reduced overall emissions that have caused record-breaking heat in recent years was largely down to China, which bucked its trend of ever-increasing coal use. Chinese emissions went up 0.9% in 2014, the same amount as the US, as it used more gas for heating. India’s emissions jumped by 7.8% while the European Union’s emissions dropped by an “unprecedented” 5.4%. The Indian increase was the largest contributor to global emissions growth in 2014 and effectively cancelled out the EU fall. Together, the four are the world’s biggest emitters, covering 61% of global emissions. Worldwide emissions increased by just 0.5% in 2014, compared to 1.5% the year before, 0.8% in 2012 and an average of 4% a year over the previous decade, when emissions grew dramatically. The slowdown last year occurred despite the global economy growing by 3%, suggesting a “decoupling” between GDP and emissions. The agency, which is considered one of the world’s top authorities on emissions data, said it appeared the world was moving into a new period of slower growth in emissions. “It is likely that the very high global annual emission growth rates, as observed in the years 2003 to 2011, will not be seen in the coming years,” it said in a statement.

The findings from the environment agency go some way to explaining the negotiating positions that countries and blocs are expected to take in Paris. While the EU, US and China are all strongly backing an ambitious climate deal, at recent G20 talks in Turkey, India was accused of holding back progress towards a Paris treaty.

However, it is clear that even if leaders of the more than 190 nations gathered at the Paris conference agree on a treaty, this will not limit global warming to below 2 degrees. Climate pledges submitted by nations in the runup to COP21 are not enough: according to UN estimates, the world would warm by 2.7 degrees even if all these pledges were implemented unconditionally. For this reason, some parties want to push for a “ratchet-up” mechanism reviewing every five years whether countries are doing enough to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Developing countries, particularly the world’s poorest countries, are especially concerned about other aspects of the climate deal to be struck in Paris: including that of climate finance. Climate financing refers to financial assistance for poor countries, for both facilitating their economies to embark on a low-carbon growth path, as well as to adapt to the effects of climate change. In the Cancun climate change conference, the international community had finalized an agreement to make $100 billion per year available for this by 2020. But it was not specifically agreed how the international community is to arrive at this sum, or which country is going to contribute what amount at which time. The NGO Oxfam estimates that public climate finance provided by developed countries was only around $20 billion per year on average in 2013 to 2014.

Beyond financing adaptation and mitigation, there is also the issue of the impacts of climate change too severe to allow for adaptation – like that of islands being washed away by rising sea levels.

In UN climate negotiating language, such effects are being described as “loss and damage” – a reference that had not been included in a first draft of the agreement. Developing countries along with small island states succeeded in adding an article on loss and damage to subsequent draft text – a paragraph they are expected to push strongly to keep in the final text. This paragraph includes the call for a facility to help coordinate efforts to address the displacement of people as a result of climate change. Suffice to say, industrialized countries are not thrilled by the prospect of rather vague, extra damage that would be difficult to put a price on, and could run very expensive. As such, this represents another potential sticking point.

Despite divergent views on many of the issues connected with striking a global climate agreement, observers are optimistic. When the international community attempted to agree a global climate deal at the climate change conference in Copenhagen in 2009, the result was a dismal failure.

The year 2015 is expected to be the hottest on record, thanks to a combination of a strong weather event and human-caused climate change. Negotiators meeting in Paris carry a huge responsibility, with a rapidly narrowing time window for closing the emissions gap and to stop global warming below 2 degrees. If the Paris Conference has not been canceled or postponed despite the terrorist attacks, it means that Heads of States are really committed in cooperating. Yet, if the willingness and the efforts will be enough to get to a result, that is just hope for the humanity but perhaps it could be the last call for the Earth.