EU between Russia and China

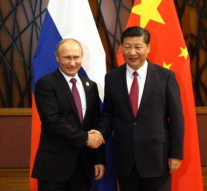

Employment and Social Affairs 6 May 2019In the new multipolar scenario, with a tough competition among United States, China and Russia, many European countries have become weaker and a potential target for the main powers. EU’s internal divisions, its attractive assets and its market of 500 million consumers make it an ideal target if it is not strongly united. The recent six-day visit to Italy and France for China’s president, Xi Jinping, could be read as a case study of one great power testing those points of weakness and wealth. Italy has become one of the first big EU country to sign the memorandum on Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), paving the way after China’s privileged role in Greece to an even stronger presence in Europe.

China is gaining a strong role also in the Balkans, a region with a lot of Chinese investments and an example of the fact that without unity and cohesion Europe could become a prey for other countries. Also, in relation with Russia, this dynamic is valid although China has a more silent approach while Moscow is in this year openly challenging EU’s order. In any case EU should seek to maintain good relations with two big global players as Moscow and Beijing, while not failing to work for a stronger unity among member states in order not to become a prey.

The EU and Beijing established formal diplomatic ties in 1975 and today EU-China relations encompass an annual summit, regular ministerial meetings, and over 60 sectoral dialogues. The EU and China are committed to a comprehensive strategic partnership, as expressed in the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation. The EU’s new Strategy on China, adopted in July 2016, has been followed by a March 2019 strategic stocktaking of the EU-China relationship by the European Commission and the High Representative. “Our partnership with China for us is a priority, and it needs a comprehensive approach to match”, recently said EU Commission president Jean Claude Juncker during the EU-China summit in April. “Our cooperation simply makes sense for both sides. The European Union is China’s largest trading partner and China is the EU’s second largest. We trade well over EUR 1.5 billion worth of goods every single day. European investment in China went up for the first time in four years in 2018”, he added. But even more difficult seems nowadays relations with Russia for the EU. On the European Union External action web site these relations are envisaged in a really short way: “The EU and Russia recognize each other as key partners on the international scene and cooperate on a number of issues of mutual interest”. This highlights that of course relations with a big and close country such as Russia are crucial for the EU. And the EU is nonetheless by far Russia’s main trading and investment partner, while Russia as the EU’s fourth trade partner is also its largest oil, gas, uranium and coal supplier, important for the EU energy needs. This economic inter-dependence of supply, demand, investment and knowledge resulted in numerous joint commitments to maintain good economic relations with a specific focus on energy cooperation offering energy security and economic growth to both sides. Sanctions undoubtedly had a huge impact: EU-Russia relations have been strained since 2014 because of Russia’s illegal annexation of Crimea, support for rebel groups in eastern Ukraine, policies in the neighborhood, disinformation campaigns and negative internal developments. The EU and Russia remain closely interdependent, but the EU applies a ‘selective engagement’ approach.

The “decline of the West” faces from the other side China’s impressive economic performance and the political influence of an assertive Russia in the international arena are combining to make Eurasia a key hub of political and economic power. Furthermore as relations between the EU and Russia remain frosty, Moscow has pivoted towards Beijing in search of deeper strategic cooperation. Russia’s calls for an integrated “Greater Eurasia” are partly a response to the launch of the BRI – an attempt by a declining power to buy time while projecting an image of itself as an equal co-architect of a fledgling Eurasian order. In reality, Russia’s fear that it will be unable to compete with the world’s second-largest economy limits its desire to push for a Eurasian free trade zone. In this situation, is not good that Brussels and Moscow continue to promote rival norms and visions for the neighborhood, making aspirations for a “Greater Europe” that stretches from Lisbon to Vladivostok implausible. A solution could be to bring closer together youngest generation, trying to bridge the existing gap launching a “greater Europe” Erasmus programs involving Russia, and even some form of cooperation in order to strengthen and to get easier cooperation among enterprises and workers between the two areas.