And now for something completely different…

Economy 23 February 2015These days it is hard to write an article about economy in Europe without mentioning Greece. After all, UK Chancellor of the Exchequer after meeting Greece’s Finance Minister said that the ongoing Eurozone power struggle is the biggest threat to the global economy. However, according to some analysts there is something even more dangerous out there.

Cambridge Economics Professor, Ha-Joon Chang in a recent interview claims that a huge financial bubble is in the making, and that sooner or later it will burst causing greater damage than the previous one. His reasoning is the following: the stock market in the US is today 20% bigger than it was in 2007; at the same time the real per capita income of the American people has grown only by 1%. Similarly, in the UK the stock market valuation is back where it was in 2007 while per capita income has not yet regained the pre-crisis level. His conclusions are that sooner or later the markets will have to adjust and the consequences will be even more severe than in previous occasions because Governments, citizens and businesses throughout the western world are still heavily indebted.

The underlying argument is that there seems to be a growing gap between the financial economy, i.e. what goes on at the level of stock exchange, and the real economy, i.e. the everyday life of citizens and business. The real economy has not recovered and is not growing robustly, at least if compared to the dynamism of the financial markets.

Economists are known to make one-too-many predictions. After all it is the best way to get at least some of them right and earn some ex-post fame. However the decoupling of financial markets from the real economy has been observed and studied for many years now. Probably the best and most comprehensive analysis of such divergence and of its consequences is the one by Hyman Minsky who identified five stages in the creation of a bubble from displacement of investment towards seemingly safe and high returns, through boom and finally panic.

The literature on financial crisis is virtually endless and can in no way be summarized here. We will however focus on some interpretations to provide some food for thought to our readers.

There is too much money out there…

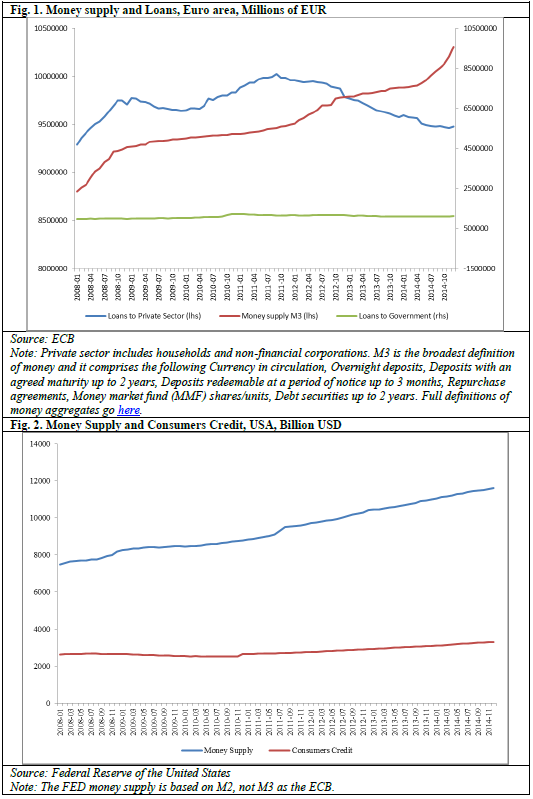

As shown in Fig. 1 and 2 below, the supply of money from the biggest Central Banks (the FED and the ECB) has increased substantially after the explosion of the 2008 financial crisis. This was necessary to provide liquidity to troubled banks and lower interest rates. It has however not translated into an increase in lending to the real economy. A major part of this liquidity has been used for other purposes.

For example, according to authoritative sources, the “excess liquidity” created by the developed economies has partially “spilled-over” onto emerging markets, creating easy credit and asset prices inflation. In other words, capital not used in America and Europe has been channelled through emerging economies, in search of higher returns.

Recently the European Central Bank has decided to engage in the so-called Quantitative Easing. Without going into the details of such operation, it suffices here to say that its expected outcome is to increase further the money supply and lower further the real interest rates. The declared objective is to boost economic recovery in the Eurozone and fight deflation. The fundamental question one should ask at this stage is: if the “excess liquidity” has failed to revitalize the economy, why should we expect a different outcome with more of the same medicine?

… it is not well spent…

The answer to this question is, in the mind of many commentators, quite straightforward: monetary policy used in isolation from fiscal policy will not be successful in kick starting a depressed economy. The argument has been developed first by John Maynard Keynes in 1936 and it is still a hugely debated topic today. In a nutshell, a financial crisis leaves the private sector with two big problems: (1) a debt “hangover”, heritage of prior excesses and (2) negative future expectations because as the economy slides into recession, aggregate demand falls and so do revenues and profits, even in sectors that had no prior excesses. These two hurdles make the private sector very unlikely to ask new loans and make new investments. What is missing therefore is demand for credit.

The solution that Keynes proposed was to have a sort of investor of last resort that would utilize private sector’s savings and Central Bank’s newly created liquidity to stimulate the real economy whereby creating jobs and income which ultimately would bring back confidence and rosier future expectations. This was the task of the Government, Keynes argued, since it is the sole institution that can take long-term risks and that can never be insolvent since it literally prints the money it uses.

So according to this interpretation of things what is missing is essentially the link between money supply and credit demand. The private sector has predictably failed to demand more credit and make more investments. And governments have not fully used their fiscal policies, despite the extremely low interest rates and the excess of liquidity, as a spur for economic growth. This is particularly true in the Eurozone as we have observed.

…and it is too free.

A different though not necessarily contradictory line of argument is that the core of the problem is the unregulated capital mobility.

Here the focus is more on flows of capital rather than on which economic actor mediates them. Even if the Government intervened to coordinate fiscal and monetary policies, asset bubbles would still be inevitable in the current context. The main argument is that full capital mobility invariably leads to imbalances. Uncontrolled and unconditional inflows and outflows of capital will always be destabilizing because of the inherent contradiction between short-term profit maximization on one side and long-term investment needs on the other.

Michael Pettis recalls some interesting historical episodes to explain how Eurozone internal imbalances have been generated through a massive transfer of capital from “core” to “periphery” Member States which produced a symmetrical combination of excess deficits and excess surpluses. He concludes that no matter who manages the investment flows, when these occur too fast and too intensely the result cannot be different from what we have observed in the run-up and aftermath of the crisis. Martin Wolf, chief economic commentators of the Financial Times, arrives at a similar reading of the events in his latest book. He concludes that unless financial markets are reined in and aggregate demand in the real economy is sufficiently boosted, the only possible outcomes are either another wave of unsustainable bubble-led growth or a prolonged period of stagnation.

We won’t dare to make further predictions here but rather leave the reader to ponder. Still it appears that while some are indicating the Moon, others are looking at the finger. Another historic recurrence.