Spain’s road to Syriza

Economy 9 February 2015The victory of the anti-austerity party in Greece is expected to have all sorts of spill-overs. One of which could be emulation in other Member States.

Eyes are set particularly on Spain, where the Podemos Party – after surprising results in the European Elections – is leading the polls and threatens to beat the incumbents from both the left and the right. We will see that there are common economic features in the two countries which may justify similar political shifts.

Remember how we set the scene for the “Greek tragedy”? We made the link between the explosion of private debt, prior to the crisis, the deterioration of the current account and the subsequent collapse of capital flows which unveiled unsustainable macroeconomic imbalances. Well, let’s take a look at Spain.

Do you notice any similarity? In Spain as well as in Greece private debt as share of GDP increased exponentially before 2008, while public debt was actually decreasing. The roles then switched after the crisis when the Government intervened to bail-out banks and pay out unemployment benefits. During the same time foreign banks’ exposure to Spain ballooned and peaked in 2008 only to collapse dramatically afterwards. Banks of Germany and France were – as in Greece – the happiest lenders to the Spanish economy. At this point, the reader won’t be surprised to learn that during the “build-up” period the Spanish current account descended into a persistent and growing deficit, reaching -10% of GDP in 2008.

However in this column we won’t dwell on the underlying causes of the crisis but rather on its socio-economic consequences and on how efficient economic policies have been in managing these consequences. For some reasons, citizens do not pay too much attention to the current account, while they are understandably much more concerned by their living standards. We can then trace some other parallels between Greece and Spain which may explain the demise of the mainstream parties in Greece and help to predict whether Spain is walking along a similar road.

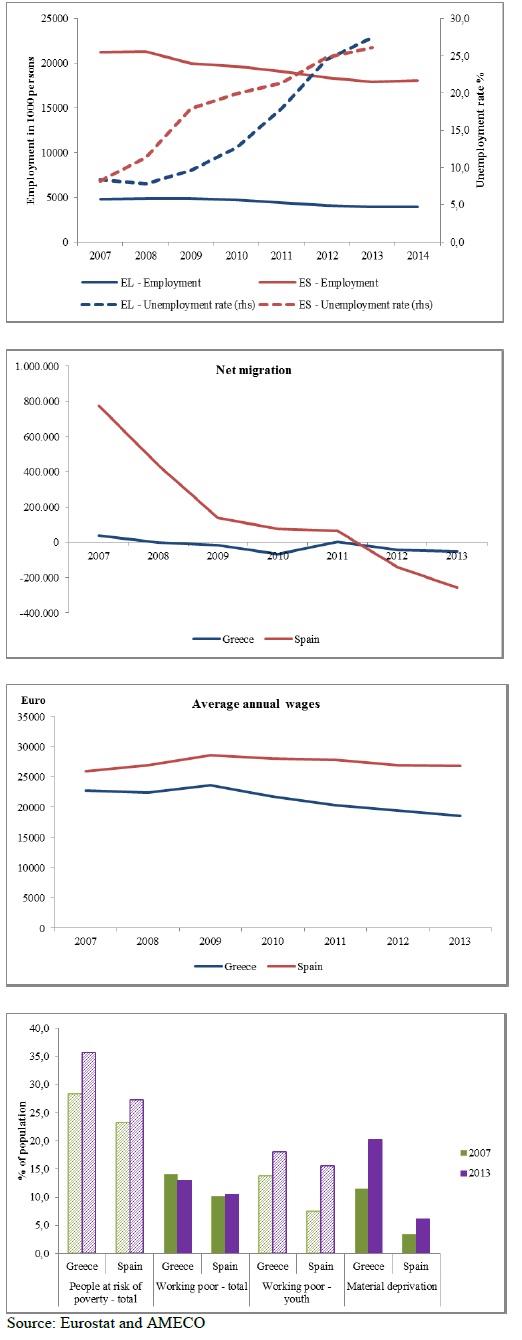

After the crisis, the labour market in both countries suffered a massive blow. The unemployment rates shot up from below 10% to more than 25%. Greece lost 20% of its labour force in terms of employed persons. Spain so far lost “only” 15%.

After the crisis, the labour market in both countries suffered a massive blow. The unemployment rates shot up from below 10% to more than 25%. Greece lost 20% of its labour force in terms of employed persons. Spain so far lost “only” 15%.

This evolution in the labour market was followed by two other phenomena. Migration flows became negative in both countries. In Greece this happened almost immediately. While in Spain the positive net migration decreased rapidly and became significantly negative from 2011.

The second related event has been the decrease in annual average wages. This happened for a combination of reasons. In part wages were deliberately cut in either nominal or real terms, both in Greece and Spain. And in part it has been a consequence of increased unemployment which puts downward pressure on salaries by weakening workers’ bargaining position. Greece’s workers lost on average about 18% of their wages while Spanish workers so far only about 7%.

Decreasing wages and increasing unemployment triggered other severe repercussions on the living conditions of both populations.

The share of population at risk of poverty increased dramatically in both countries, although much more in Greece than in Spain.

At the same time people suffering from material deprivation (defined as the impossibility of purchasing a basket of items considered as essential) doubled in both countries, although the levels remain significantly higher in Greece than in Spain.

Finally and possibly more interestingly, the share of working poor over the total population did not increase in either of the two countries. However when looking only at the young population, age 18-24, the share of working poor went up significantly and in terms of dynamics, the change was much more severe in Spain than in Greece.

So in sum, the crisis has dragged on for seven years now and has made its victims, in particular among the workers and the youth who face one of the three options: migration, falling wages or unemployment. Not surprisingly, citizens of Greece expressed their resentment at the elections. Spain’s socio-economic conditions are not as severe as in Greece, although their trend has clearly pointed in the same direction. In December this year, the Spanish electorate will have a chance to say what they think about it.

Economic commentators have noticed that Greece is slowly going back to positive GDP growth this year; and that Spain will also experience some growth thanks especially to its positive current account balance. True. But as the Nobel Prize laureate Joseph Stiglitz has noted: “every downturn comes to an end. Success should not be measured by the fact that recovery eventually occurs, but by how quickly it takes hold and how extensive the damage caused by the slump“. In other words, the effectiveness of economic policies should be measured by their ability to soften the impact of the crisis and rapidly resume the growth path. The evolution of some of the main social indicators presented above seems to suggest that in both Greece and Spain economic policies have failed the “effectiveness” test.

The follow up question should then be to ask “why” they have failed. We have already tried to provide some elements to answer such question without the ambition of being exhaustive. This time we leave the reader with the words of a more prominent thinker:

Imagine, for example, an unexpected permanent fall in Spanish aggregate demand that the other EMU countries escape. An idiosyncratic national real shock such as this would not cause much depreciation of the euro against outside currencies, nor would it trigger monetary easing by the ECB. If EMU were an optimum currency area, Spanish workers would migrate to other EMU countries rather than facing unemployment at home. In reality, however, out-migration would be minimal, and unemployment would therefore persist until Spanish prices and costs had fallen enough to create an export-led recovery. The deflation process is a lengthy one.(…)

[This paragraph was written by Maurice Obstfeld, Professor of Economics at Berkley in a paper called Europe’s Gamble, published on the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. In 1997.]